The History Of African Americans In Beloit

Introduction

African Americans have a long and rich history in the city of Beloit. They were here from its beginning. There are as many variations to the African American story in Beloit as there were families who lived in and around its vicinity. During the nineteenth and early twentieth Centuries, families from southern locales and elsewhere who made Beloit their home had a common desire: to strive for opportunities that were better than those afforded them in their former places. They sought control of their own destinies through advancement in employment, education, social relevance and a voice in local politics where they lived. In the early twentieth century, European peoples’ ocean immigration to the United States at Ellis Island and other eastern seaports paralleled the aspirations for these African Americans’ cross-country migration north, leaving from all points south of the Mason-Dixon Line, and arriving at the Northwestern Railway Depot at Beloit.

Here resided HOPE and OPPORTUNITY.

Here was a new world with LESS FEAR and VICTIMIZATION.

Here was BELOIT WISCONSIN.

Remembering Our Veterans

"Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship." - Frederick Douglass, from his Speech, "Should the Negro Enlist in the Union Army?", National Hall, Philadelphia (6 July 1863); published in Douglass' Monthly, August 1863

African Americans have fought for the United States throughout its history, defending, serving and risking their lives for a country that in turn had denied them their basic rights as citizens. Despite policies of racial segregation and discrimination, African American soldiers played a significant role in protecting our country’s freedom and democracy. On July 26, 1948, an executive order by President Harry S. Truman began the process of abolishing racial discrimination in the United States Armed Forces. The executive order was to establish “equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed forces without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin.” Because of resistance from white soldiers and military personnel who refused to comply, it was years before this order became a major transformation for African-American soldiers. The Secretary of Defense, in 1953, announced that segregation officially ended abolishing the last all-black unit.

Sadly, when African American soldiers returned home, they encountered more racism and segregation. Rather than being honored and respected like the white veterans, they faced an ungrateful nation often rejected and ostracized them.

McCords Proudly Fought for Country

Jessie and Mariah McCord, who came to Beloit in 1916 as part of the Great Migration from Pontotoc, Mississippi, were the parents of eleven children. Their sons Richard and Ernest enlisted into the Army in 1917 and both were members of the 365th Infantry 92nd Division during World War I. The 92nd Infantry Division, established on November 29, 1917, was a segregated infantry division of theU United States Army, this division included the 365th Infantry Regiment. Rockford’s Camp Grant had segregated housing and recreation buildings for the African American soldiers. Many times, the African American soldiers were not provided the equipment and weapons they needed to accomplish the assignment given. Although the 92nd was comprised of all African American enlistees, as well as it’s junior officer, the higher-ranking officers were all white. The 92nd fought in France during World War I and World War II.

The Beloit Daily News featured a story on the McCord family on February 26, 1994, Former slave found new life in Beloit. The article interviewed Richard McCord’s children Jesse E. McCord and Ida Savage. Jesse provided a November 1917 photograph of his dad and Uncle Ernest taken with their squad at Camp Grant in Rockford, Illinois. The 1910 United States Census shows Richard and Ernest have a younger brother named Jesse B., age 9. A gravestone at Eastlawn Cemetery reads: Jesse B. McCord. Wisconsin. PVT U.S. Army, WW II. April 7, 1900 - Feb. 27, 1969. The 1994 Beloit Daily News article doesn’t mention this brother, Jesse B. McCord, but records show that he is the son of Jessie and Mariah McCord.

Richard McCord’s four sons John, LeRoy, Jesse and Clinton followed in their dad’s footsteps and joined the Army serving in World War II. In Jesse’s interview for the Beloit Daily News article he stated, “My father died before the second World War.” But he shared his father’s pride in the country, and saw action in Africa and Europe. “I had three other brothers-John, Leroy, and Clinton-all of us fought in World War II and were drafted out of Beloit.” All four went to north Africa, Italy and Germany, and fought in the invasions of Sicily and southern France.

“I’m proud of my father and brothers who served their country in the military, and I’m proud of our history.” said Ida McCord Savage.

The following McCords are buried at Eastlawn Cemetery:

-John McCord

PFC U.S. ARMY

Nov.19, 1914 - Oct. 25, 1968.

-Lee Roy McCord

PFC in the US Army.

February 27, 1916 - November 15, 1974

Lee Roy McCord’s name appeared on several vessel manifest lists of employed crew members. The above manifest is for the transport ship George W. Goethals that sailed from the port of Bremerhaven, Germany on April 12, 1947 arriving at New York, N.Y. on April 25, 1947. It listed his position on the ship as 3rd Cook on this manifest. Italy and France were other countries that Private McCord traveled to during his service in the U.S. Army.

-Clinton R. McCord

PFC WWII

April 11, 1921 - Nov. 15, 1961.

-Jesse B. McCord

PVT U.S. Army WWII

April 7, 1900 - Feb. 27, 1969.

Buried at Oakwood Cemetery:

-Ernest was a World War I Veteran, serving as a Private with the 365th INF. 92nd DIV. Private Ernest McCord enlisted October 26, 1917 and was discharged on January 23, 1919.

Jarrett Bond

Jarrett Willis Bond was born to William and Julia Bowling Bond on January 9, 1889 in Beloit. He enlisted into the U. S. Navy on March 12, 1913 and served in World War I until he was honorably discharged on March 10, 1917.

Jarrett’s rank in the Navy was that of Chief Water tender for the ship’s boilers on the Battleship Florida. Photo ca. 1918.

Bond died on January 11, 1966 and is buried at Oakwood Cemetery.

Jarrett Bond came from a family of veterans, starting with his grandfather Silas Bond Sr. and his father William Bond.

Silas Bond Sr. And his wife Lucretia

Silas Bond Sr. was born in 1830 and lived in Shelby County, Ohio according to the U.S. Civil War Draft Registration Records. Married and the father of four children, he enlisted as a volunteer on September 28, 1864 at the Army headquarters in Columbus, Ohio. Private Bond served in the Civil War with the 44th U.S. Colored Infantry, a Union troop organized in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Silas Bond Sr. died on May 6, 1865 from complications due to typhoid fever and pneumonia. He was buried at Chattanooga National Cemetery in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Military records indicate that Silas had several brothers that also fought in the Civil War.

William Bond, Jarrett’s father, was born in Shelby County, Ohio on April 22, 1856. William lived in Ohio with his grandmother after the death of both parents. After her passing, young William migrated to Roscoe, Illinois in 1865. He moved into the homes of several families, worked on their farms and attended school.

At the age of 21, William enlisted in the U.S. Army and served with the 9th U.S. Cavalry, one of the original four segregated regiments of the regular U.S. Army set aside for enlisted African American men. The 9th U.S. Cavalry regiment saw combat during the Indian Wars, fighting mainly against Indians in the West, providing security for the early western settlers, and they also protected the friendly Indian tribes that settled in the Midwest from settlers seeking to steal their land.

William Bond married Julia Anne Bowling, the daughter of Joseph Bowling, one of Beloit’s early African American citizens. He died December 28, 1958 and is buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

John Strothers a Civil War Veteran

John Strothers was born in Virginia during the time of slavery, in 1845. He came to Beloit in 1863 with the Reigarts, a prominent white family from Pennsylvania.

On August 6, 1864, in Janesville Wisconsin, eighteen-year-old Strothers enlisted in the United States Army to become a volunteer substitute for John R. Reigart, one of the family members that brought Strothers to Beloit. Strothers enlistment acknowledged that he would serve as a soldier in the Army for one year in lieu of John R. Reigart. Military enrollment laws allowed able-bodied men, who could afford it, to avoid military service for a commutation fee of three hundred dollars, or allowed a man to enlist in the place of another by compensating him, sometimes up to one thousand dollars or more depending on the length of service. Unable to serve along-side with the Union white soldiers, Private John Strothers was assigned to the 18th United States Colored Infantry Regiment in Missouri. Strothers fought in the Battle of Nashville, which took place from December 15-16, 1864. On February 23, 1865, Private John Strothers was appointed Corporal.

Further inspection of the record revealed that three other African Americans from Beloit of equal age, Peter Dabney, Moses Nelson and James Reed also enlisted and were assigned to the 18th Infantry as substitute soldiers the same week as Strothers.

Corporal John Strothers was mustered out on August 5, 1865 at Chattanooga Tennessee. He had served his one year term of service as a substitute volunteer.

Described as being industrious, John Strothers returned to Beloit where he learned the blacksmith trade under Filas Malone, an African American businessman and also became a fine woodworker. It is written that Strothers brought personal property in South Beloit and worked on a farm for a Mr. Colt, where he plowed much of the land that is currently South Beloit. He eventually married Miss Minnie Benson, who came to Beloit in 1864 from Cape Girardeau, Missouri and had eight children.

Until his death on February 27, 1927, Corporal John Strothers marched in every Beloit Memorial Day Parade as a proud veteran along-side the soldiers. He is buried at Oakwood Cemetery.

WISCONSIN HISTORYMAKER,

GENERAL MAJOR MARCIA ANDERSON (RET)

‘Commands THE JOURNEY AHEAD’

(The following article was featured on the Wisconsin Department of Veterans Affairs website, dated February 19, 2020).

Marcia Anderson was just looking to take a science class to fulfill her undergraduate science requirement for her art degree. She was not interested in the traditional science class with test tubes and microscopes, rather she signed up for a military science course that would fulfill the requirement. That class set her on course to becoming the first African American in the United States Army Reserve to attain the rank of major general, taking her place in our nation’s history.

Anderson’s father, Rudy Mahan, served in the U.S. Air Force as truck driver during the Korean War and her brother served in the Marines for 12 years. Her father had a dream of serving as a bomber pilot, but he didn’t have access to programs such as Officer Candidate School, which he would need a commission in order to apply for flight school.

Growing up in Beloit, Anderson says that her grandmother and mother were the greatest influences in her life. Both women were very assertive people, who believed that she could do anything and both made sure she had plenty of opportunities - when they could afford it- to

attend arts and sporting events. She especially shared a deep bond with her great grandmother, whom they called “Mother Dear,” whose wisdom and insights into life helped Anderson become who she is today.

Things weren’t always easy for Anderson, who was held back in kindergarten when her teacher told her mother that she was a bit slow. That setback became a powerful motivation for her. She was determined to prove that teacher wrong.

Growing up, Anderson never saw herself as a leader, nor did she see herself in charge of anyone but herself. She had done a little camping in the Girl Scouts, but nothing that would prepare her for what she would experience in the military.

That all changed in 1977. While attending Creighton University in Omaha, she accidently signed up for ROTC for a science credit. The training made her step outside her comfort zone and forced her to take leadership roles as a cadet. She had to quickly learn how to motivate other people, figure out a plan, and execute it, sometimes with limited resources and information. She realized that she liked the physical aspects of the training, learning new things like rappelling, map reading, first aid, firing a weapon, and “camping.”

Most importantly, to her, was how much she learned from and admired the other cadets. They knew they were all part of something much greater than themselves. And the military's structure appealed to her. So she joined the United States Army in May of 1979 when she received her Commission as a 2nd Lieutenant upon graduating from Creighton University.

Again, things weren’t always easy. During her initial years of service in the 1980s, there were many people who did not welcome her- or other women for that matter- as a soldier, value her contributions, or believe they could trust her to do the right thing. While she was a captain, her superior, a lieutenant colonel, introduced her to his staff sayin that he was “forced” to take her. She recalls others took credit for her work, diminished her accomplishments, and told her that she was taking a position from a male officer who deserved it more.

Comments like that made her even more determined to learn the profession of arms, excel at every task, and demonstrate that she had earned and deserved a leadership role.

Over the next thirty years, Anderson climbed the ranks of the US Army Reserve, defying the odds and the attitudes.

On October 1, 2011, Marcia Anderson made history when the United States Army Reserve promoted her to major general during a ceremony at Fort Knox. She was to be stationed in Washington D.C. as the third-highest ranking officer in the Army Reserve. She was the first African American to achieve this rank.

Humble, she felt very responsible to all those who had preceded her in service, such as the women of the 6888th Postal Battalion, the Tuskegee Airmen, the Buffalo Soldiers, the Montford Point Marines, and countless people who served without recognition or thanks. She was also grateful to those women in Beloit who set her up for success: her mother, grandmother, and Mother Dear. She promised she would never do anything while serving that would dishonor or minimize all of their sacrifices and each day she led proudly in their honor.

In 2016, after a thirty-six year career, General Anderson retired from the Army Reserve. During her years in service, she earned the Distinguished Service Medal, the Legion of Merit with two oak leaf clusters, the Meritorious Service Medal with three oak leaf clusters, the

Army Commendation Medal, the Army Achievement Medal, the Parachutist Badge, and the Physical Fitness Badge. Later that year, Secretary of the Navy Richard Spencer named her to be the sponsor of the USS Beloit, an honor bestowed on her for her ties to Beloit and her service to her country. She is now permanently part of that ship’s history.

Like those before her, General Anderson shares what she has learned with her fellow veterans: “Each one of us are unique and we need to remember that we are very special. Out of a population of over three hundred million, less than one percent of the people in this country have served in the military. Each person who has served has been trained and ‘KNOWS’ how to lead and handle stressful situations. Be proud of your service. You earned that right.”

George Marion Ingram

(The following information was taken for the Beloit Daily News (June and July 2016) and his obituary on the Hansen-Gravitt Funeral Home website).

George Ingram was born on March 10, 1929 in Pontotoc, Mississippi, the son of Frank C. and Viola H. (Howard) Ingram. As a young man George enlisted into the United States Air Force and attained the rank of A1C (Airman First Class).

On July 26, 1951 George was assigned to the 34th Air Transport Squadron at McChord Air Force Base in Washington. He was scheduled to be part of the crew on the flight of a Douglas C-124 Globemaster departing on November 22, 1925 from McChord Air Force Base and scheduled to land at Elmendorf Air Force Base in Anchorage, Alaska. On the flight manifest George was listed as the "Loadmaster". During the flight it is documented that the aircraft encountered extremely severe weather conditions. Around 4pm on November 22, 1952, a distress call from the C-124 was faintly heard by a Northwest Orient Airlines Commercial flight. The reception was poor, but the Northwest captain made out the sentence: "As long as we have to land, we might as well land here." No further communication from the Air Force C-124 was ever heard again and subsequently the plane never arrived at Elmendorf.

Due to the poor weather conditions in the area at the time of the disappearance of the C-124, search efforts couldn't begin until three days after the plane went missing. The crash site and wreckage were discovered on November 28, 1952 by an officer of the 10th Air Rescue Squadron along with a member of the Fairbanks Civil Air Patrol. The pair spotted the tail section of the C-124 sticking out of the snow at an elevation of 8,100 feet, close to the summit of Mount Gannett. On December 9, 1952 a recovery crew once again reached the tail section, but found no trace of survivors or any additional wreckage. They were forced to call off any further search and rescue operations by the inhospitable conditions and to return to base camp. Shortly thereafter, the U.S. Air Force declared that the 11 crew members, and the 41 other service members were deceased. All traces of the plane and its passengers were lost for another 60 years.

On June 9, 2012 the wreckage was spotted by the crew of an Alaska National Guard Black Hawk UH-60 Helicopter during a routine training mission. It was located 45 miles east of Anchorage, Alaska at the tip of the Colony Glacier, where the glacier meets Inner Lake George. The rediscovery site was more than 12 miles from the original location because it was resting on the moving flow of the Colony Glacier for the past 60 years. On June 28, 2012, the U.S. Military announced the discovery of the wreckage. Shortly thereafter a recovery operation was started by the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command. On June 18, 2014 the Department of Defense announced that the remains of 17 of the victims had been identified so far through DNA samples and that the remains would be returned to their families.

Military honors were provided by the U.S. Air Force as Airman George Marion Ingram's body was flown into Milwaukee with a military escort aboard a civilian flight. From there, Rock County Sheriff's Department and the Patriot Guard Riders escorted the procession to Beloit. Airman First Class George Marion Ingram was laid to rest on July 28, 2016 in the Veterans Section at Eastlawn Cemetery.

Zac Bellman/Staff Writer Beloit Daily News Jul 29, 2016

Pallbearers from the 375th Air Mobile Wing Honor Guard hoist the remains of George Marion Ingram to be laid to rest at Eastlawn Cemetery Friday.

African Americans in Beloit during the 1840’s - 1860’s

Before discussing the African American families living in Beloit during the 1850’s, we need to point out what was taking place in American history. In 1850 the national debate to limit or abolish slavery was inflamed by the new Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. The Fugitive Slave Act enacted in 1793 had become weaker in power having met resistance from many Northern states and those strongly opposed to the institution of slavery. The 1850 law now mandated the role of the federal government to track runaway slaves, even in free states, and return them to slaveholders. It gave slaveholders greater power and the slave no power at all if seized. Wisconsin, a free state, became the destination of many slaves seeking asylum from the brutality and inhumane treatment endured at the hands of their slave master. Undocumented free persons were at risk for abduction, without regard to their free status, and they could be put up for sale to slavers.

Wisconsin, refusing to be complicit in the institution of slavery, passed new measures intended to bypass and even nullify the law. Several states including Wisconsin passed “The Personal Liberty Law” making it difficult for slave masters and slave catchers “agents” to enforce the fugitive slave law. It gave the runaways the right to a jury trial and also protected free blacks (an example is Solomon Northup in the 12 Years a Slave movie.)

Despite the division in America caused by slavery, free black families continued to arrive in Beloit from places like Alabama, Arkansas, Missouri, North Carolina, and Ohio. By 1855 Beloit had a population of 2,753 of which 18 were African Americans.

In 1848 Wisconsin, a free state, became the thirtieth state admitted to the Union. Eight years later in 1856, Beloit was incorporated as a city. In researching the history of African Americans in Beloit, the same names kept appearing in all the articles I read. Those names were Emmanuel Craig, Gilliam Perry, Joseph Bowling, Sam Davis, Stanton Keyes, Dave Young, William Atwood Waffles, Johnny Strothers and Filas Malone. I have not been able to substantiate the years of their arrival to Beloit, but through census records, newspaper articles, church records, Beloit City Directories and cemetery records, I have been able to piece together some assemblage of the history of the first African American families that made Beloit their home. My research found very little documentation that recorded the white host families for many of the first African American families that lived in Beloit in the late 1830’s-1870. It is my belief that white families who settled in the village of Beloit brought many of the African American families along with them. Enjoy reading the following stories on two early African American families that made the city of Beloit home.

Stanton and Zilphia Keyes

“For many years after 1850 much of Beloit’s cord wood was sawed by Stanton Keyes. He and his wife, Zilphia, were highly religious and were charter members of the Bethel A. M. E. church. Keyes was only four feet in height and weighed 170 pounds. On church days, he always dressed completely in white. He was widely known for the prayers he made, and could be heard more than a block away.”

This is a paragraph from an article entitled, “Colored Families Came Early To Beloit; Some Were Brought By Returning Veterans Of War” that was published in the Beloit Daily News on May 21, 1936.

Like most African Americans, the Keyes were first found in the 1870 U. S. Census living in the 2nd Ward of Beloit. It’s not uncommon when researching an individual to find variations of the spelling of their name and the documents often will have different birth years and birthplaces for a person.

Stanton Keys

Age in 1870: 23

Birth Year: 1847

Birthplace: Alabama

Occupation: Works at all work

Personal Estate Value: 400

Real Estate Value: 800

Spouse: Zilpha Age: 24

Birthplace: Tennessee

Occupation: Keeps house

The Keyes are listed on the 1875 Wisconsin State Census, 1 colored male and 1 colored female.

The 1880 U.S. Census listed the following information:

Stanton Keyes Age: 45

Birth Date: Abt 1835

Birthplace: Alabama

Parent’s Birthplace: Alabama

Occupation: Works by the Day

Spouse’s name: Tilpha Keyes

Age: 32

Birth Date: Abt 1848

Birthplace: Alabama

Parent’s Birthplace: Virginia

Occupation: Keeps house

The Keyes are listed on the 1885 Wisconsin State Census, 1 colored male and 1 colored female. Documents never indicated that the Keyes had children.

The 1890 Hand Book of Beloit (City Directory) shows Stanton Keyes living at 716 Park Ave, occupation Laborer.

There is a record of Stanton Keys in the U.S., Civil War Draft Registrations Records, 1863- 1865, with this document, it puts Stanton Keyes was living in Beloit in 1863.

Name: Keyes, Stanton

Residence: City of Beloit

Age as of July 1863: 28

Race: Colored

Occupation: Laborer Married

Place of Birth: Alabama

The following information on Mr. and Mrs. Stanton Keyes was found in the Beloit Historical Society files

1st Congregational Church bulletin

Historical Notes:

One of our own members, Dr. Henry P. Strong (1855) assisted a slave couple, Mr. and Mrs. Stanton Keys, to escape slavery in Alabama and Arkansas. The couple had escaped to Cairo, Illinois at the outbreak of the Civil War where they labored for army officers. Dr. Strong assisted them to come to Beloit where they proved worthy, sober, quiet and industrious. Stanton Keys, a frugal and faithful man learned a half dozen trades which he could perform fairly well. He always, by habit, returned ten hours of hard labor for ten hours of pay. He could be found sawing wood at 5 AM., at noon and later at nine PM. During the summer months, he labored on an average sixteen hours a day, from dawn to dusk. Shortly the couple had saved sufficiently to partly purchase a home at 716 Park Avenue. Then for some years they kept busily engaged in paying off this debt.

In later years, they were able to add a new front to the old homestead. Then Mrs. Keys conceived the idea of purchasing a piano which she learned to play. Upon becoming adept at this she started to give piano lessons to other aspiring students. Foresighted the couple purchased two cemetery lots and laid aside $70 for their funeral expenses. However, Mrs. Stanton Keys was better at working and earning than managing the family finances. Three times the couple were declared bankrupt after falling into the hands of money lenders, with usury in mind and with health quacks.

Mr. Stanton Keys, being a very religious individual and eloquent in prayers, finally went blind. The burdens of life became too great and he went out of his mind shortly ending in a merciful death.

Mr. and Mrs. Stanton Keys were a notable couple and their disappearance from Beloit history was considered a real loss having possessed virtues which fellowmen should all be the better for striving to possess. The couple outlived their Congregational benefactor.

By: M. Walter Dundore

The name of Stanton “Keys,” mentioned in the calendar of last week, was spelled by his contemporaries Keyes. (Beloit City Directory, 1889). He was a figure in the social life of the time. The following is a comment from a letter of R. D. Salisbury to H. S. Fiske, BC ’81 and ’82, respectively, on a reception given by Sereno T. Merrill at his home on the NE corner of Park Avenue and Chapin Street, for his eldest son, George S. Merrill and his bride, Lila Bushnell, daughter of the Reverend George Bushnell of the First Congregational Church. This letter was written September 24, 1882.

“Tuesday night, ‘Sereno’ gave Lila & her husband a reception, or as his respectful daughter called it, a ‘blow out.’ There must have been five hundred there. Things— some of them—were done up in style. Stanton stood at the outer door to tell people as nearly as I could make out, that there was a door thro’ which they might pass. Young Wurtz was within to tell people to go upstairs, & J. Knapp introduced each to Mr. Merrill, who stood next the door, altho’ he had known them all his life. Mrs. Merrill was indisposed & consequently did not appear in the ‘row.”

(The identification of Stanton as Stanton Keyes was furnished by the editor of Salisbury letters by Miss Helen Merrill.)

Contributed by HLDR

The following article appeared in Daily Register-Gazette (Rockford, Illinois) on Monday, November 16, 1896, Page 1:

Beloit, Wis., Nov. 16. Stanton Keyes, a colored man who has been insane for the past two or three years, died yesterday at the county asylum. He was well known by all the colored people in this section.

Both Stanton and Zilpah (Zilphia, Zilpha, Zelpha) are buried at Oakwood Cemetery in Beloit. Their graves are marked with a small headstone. Sometime after the Keyes’ death, a large beautiful and stately monument with the following inscription was added.

STANTON AND ZILPAH KEYES

AGES UNKNOWN

DIED

NOV 23, 1896 / NOV. 24, 1895

Born in and escaping

from slavery, they came

to Beloit in 1862, becoming

useful and worthy citizens.

KEYES

It is unknown as to who honored them in their death with this monument. It’s truly a testament to the love and respect that a person(s) had for the Keyes.

Joseph Bowling

In 1848, Joseph Bowling came to Beloit as a free African American man. The Beloit Daily News article, “First Negro Family Came to Beloit in the Late Thirties” that was published on February 11, 1941, included the following on Joseph Bowling: “Joe Bowling came to Beloit around1846 and became the first bootmaker in the city. The fame of his superior boots and shoes reached far beyond the city’s borders and helped to establish an early reputation for Beloit as the home of good shoes. He built a fine brick house on Fourth street south of Portland avenue and the building is in good condition today.”

Joseph Bowling settled down in Beloit, established a successful business and married in 1857. Mrs. Rubie Bond, whose husband Franklin Bond is a descendent of Joseph Bowling, wrote in her genealogical information the following: “Mary Jane Moncrete was born in 1831 in Alsace-Lorraine, Germany. Her family migrated to Pennsylvania, then to Beloit, probably Newark Township.” Not much more is known about Mary’s family name or the year they came to the Beloit area.

The 1860 U. S. census listed Joseph A. Bowling as a 35-year-old mulatto and his place of birth was North Carolina. It states his wife Mary was 29 years old and Germany as her country of birth. They were the parents of two sons; Joseph, 3 years old and John 10 months old, living in the city of Beloit. It listed Joseph as a shoemaker, the value of real estate was $500, the value of personal estate was $200. Joseph owned and operated a bootmaker shop at the southeast corner of State Street and Grand Avenue. The 1867 Rock County Almanac and Business Directory listings under Boot and Shoe Dealers and Manufacturers included, Bowling J. A., 15 State.

Mrs. Rubie Bond wrote that Mr. Bowling was baptized and became an active member of the First Baptist Church in Beloit. Her information also notes that Joseph Bowling owned a broom farm on the westside of Beloit on the Wisconsin-Illinois state line.

According to the 1870 U.S. Census, Joseph and Mary Bowling were the parents of six children, ranging in age from 12 years of age to 1 years old. The children’s names were Edward, Henry, Jane, Julia, Willie and Judson. The enumerator listed the Race for the entire family as Black. Joseph’s occupation is listed as shoemaker and Mary’s occupation as keeps house and their real estate value is $500.

The Bowling family is next listed in the June 1875 Wisconsin State Census. J. Bowling is listed as the Head of Family, no other names are listed. But, on this 1875 census next to J. Bowling’s listing there is a section for Aggregate Population in which it listed 1 white female, 4 colored males and 1 colored female. Obviously, Joseph Bowling’s family.

The 1880 U. S. Census is the last time Joseph A. Bowling is listed. Joseph and his wife Mary are living on Fourth St with five of their children. Joseph’s occupation is still listed as a shoemaker, Mary as keeping house, their 20 yr old son Henry’s occupation is listed as “barber”. Their 18 and 16 yr old daughters, Jenny A. and Julia A. are listed as “at home”. The youngest two sons, Jarrett 14 and Judson 12, occupation is listed as “works in sash factory.” This census listed all family members as “M” for mulatto except Mary who is listed as “W” for white.

Joseph A. Bowling died on May 23, 1884 in Rockton, Winnebago, Illinois. His Matters of Estate and probate records dated May 26, 1885, case number 2644, are recorded at the County Court, Rock County, Wisconsin. The 1890 Handbook of Beloit City Directory listed a Mrs. J. A. Bowling living at 629 Harrison Ave. Mary Bowling’s daughter Jane (Jennie) and her husband Emmanuel Abraham were living as a neighbor at 628 Harrison Ave.

Mary Bowling died on December 29, 1898. She is buried next to her husband Joseph Bowling at Oakwood Cemetery in Beloit, Wisconsin. The grave marker has the name Mary J. Bowling. Additional information from findagrave.com gives her date of birth as August 12, 1829 and place of birth, Germany.

Oakwood Cemetery is also the final resting place for four of Joseph and Mary Bowling’s children. According to the grave markers buried are Henry 1860-1926, his wife Alice 1862-1919, Judson 1869-1932, Joseph E. 1858-1936 and their daughter Julia Ann Bond 1865-1951. Their daughter Jennie Abraham Bond is buried in South Bend, IN, 1663-1916 and their son Jarrett Willis (J. Willis, Jay W.) is buried in Waukesha, WI. 1866-1957. The Bowling children all married and five of the six had children. Julia Ann Bowling married William Bond, who came to the Beloit area around 1864. The Bond’s made their home in Beloit and were the parents of eight children. It is from the union of Julia and William Bond that there are descendants of Joseph and Mary Bowling still living in the area today.

The McCord Family Comes to Beloit

At the peak of the African American migration in 1917 from the South to the North, Beloit Wisconsin was a city that became the destination for many. Some northern manufacturing plants recruited African Americans from the south to come north to work in their factories due to the loss of white workers who were away fighting in World War I. Fairbanks Morse & Company, located in Beloit, was not only in need of workers to replace the labor force but also to fill the demands of machinery that was manufactured by Fairbanks. They employed an estimated 2,300 workers in 1915 of which only six were African Americans. The 1910 U.S. census recorded the population of Beloit to be 15,125, of which only ninety-four were African Americans. In 1916, Fairbanks enlisted the aid of a young African American from Pontotoc, Mississippi by the name of John McCord to help recruit black labor. This was the beginning of the Great Migration to Beloit for many African Americans. Eager for an opportunity to escape the Jim Crow laws of the South and begin a better life for themselves and their families.

John McCord

One of the early families to migrate North was the family of Jesse and Moriah McCord in 1916. Jesse and Moriah (Barr) were both born into slavery in Pontotoc, Mississippi. In 1937, the McCords were featured in a Beloit Daily News article for their 55th wedding anniversary. The article gives a peek into the life of Jesse and Moriah upon their arrival to Beloit.

NEGRO CONGREGATION TO HONOR AGED COUPLE BORN IN SLAVERY

Article published in the Beloit Daily News on November 30, 1937

Jesse and Moriah McCord sit on the front porch of their home located at 1418 Athletic Ave. in this photograph from 1937, the year they celebrated their 55th wedding anniversary. The couple was born into slavery near Pontotoc, Mississippi and were children when the Civil War ended in 1865. They moved to Beloit, WI during the Great Migration of African Americans to the North.

Photos courtesy of Philip Bryd, son of Fannie Byrd

Beloit’s Early Families

When the territory of Beloit was founded in 1836, African Americans witnessed its inauguration. Beloit officially became a village in 1846. In 1848 Wisconsin, a free state, was admitted to the Union as the thirtieth state. Eight years later in 1856, Beloit was incorporated as a city. I have not been able to substantiate the years of their arrival to Beloit, but through census records, newspaper articles, church records, Beloit City Directories and cemetery records, I have been able to piece together some assemblage of the history of the first African American families that made Beloit their home. My research found no documentation that recorded the white host families for many of the first African American families that lived in Beloit in the late 1830’s-1870. It’s hard for me to imagine that during this time period African Americans were freely traveling with their families from state to state in search of better opportunities. The risk and punishment of escape was too great for many slaves, free or not to chance during those years. Therefore it is my belief that prominent white families who settled in the village of Beloit brought many of the African American families along with them. Many of them were employed as laborers, servants, domestic workers or farm hands. Through my research the historical records did not define their original relationships with their host families.

1887 Map of the city of Beloit

Several prominent white residents of Beloit have written articles on the history of “Negros” coming to Beloit. M. Walter Dundore wrote a paper in November, 1968 entitled, “NEGRO HISTORY OF BELOIT.” Below is a portion of what Mr. Dundore wrote; “before and during the Civil War, officers and doctors helped negro couples escape from the south. During this time period when these white men returned home they brought with them the negro men servants back with them. The more prosperous men such as doctors, lawyers, bankers depended on these negro families that came to Beloit. The negro men became coachmen, stablemen and gardeners while their wives became house servants, keeping house and caring for their children. There was a truly fraternal feeling on the part of the white man toward his colored workers. Houses were built for the negro family, educated white women taught the negroes to read and write. Dr. H.B. Strong build a home for his negro servant family. As this farming area raised. many horses (for use in lumber camps, overland Gold Rush caravansor trains, local dray and farm work, carriage horses, racing),” these job opportunities were filled by Negroes. One of the first people of color arriving in Beloit from the 1830s and 40s was a man by the name of Emmanuel Craig.

Emmanuel Craig

An article dated February 11, 1941 was published in the Beloit Daily News, entitled, “First Negro Family Came to Beloit in the Late Thirties.” Reverend Hermes Zimmerman, an African American pastor of one of the local churches in Beloit, compiled and submitted historical information on early “colored” families in Beloit. The following is an excerpt from that article, “Mr. and Mrs. Emanuel Craig were the earliest colored people to settle in Beloit in the late 1830’s. Mr. Craig was born about 1770, a few years before the War of Independence and could remember conversations back in the nation’s infancy. He and Mrs. Craig lived on Portland avenue. He was a coachman and always wore a uniform with a high black stove pipe hat. He lived to be 115 years old and died in 1885.”

Another resourceful article that was printed in the Beloit Daily News on May 21, 1936, pages 12-13, was entitled ““Colored Families Came Early To Beloit; Some Were Brought By Returning Veterans Of War.” The article begins with the following paragraph, “When Beloit was a village only a few years old one of its best-known residents was an old colored coachman with his high silk stove-pipe hat; a decade later, old folk’s legends say, southern slaves whispered of the “underground railway” and a “station” at a place called Beloit, and it is said that some of the daring run-aways hid out here on their flight to Canada and freedom. Before the Civil war colored people lived here; during and after the war more families came, and in more recent years Beloit has become the home of a large colored population.” The old colored coachman, is referring to Emmanuel Craig, who is believed to be Beloit’s very first African American resident. The article further describes that Mr. Craig was born in the south before there was any United States Of America, about 1770. The writer writes “The story of his early life and how he brought his wife to Beloit must have been a thrilling tale, but it is lost, as there are no Craig descendants here.” Little has been recorded or written about Mr. and Mrs. Craig, the four short paragraphs in these two Beloit Daily News articles were amongst the few details that I could find on the Craigs. The article describes Mr. Craig as Beloit’s coachman, his dress and deportment was immaculate as he rode most of the early settlers through the shady streets in his shining horse-drawn carriage. According to the article about 1885 the old couple died, the wife at the age of 93, the husband at the Methusalan (Methuselah) age of 115.

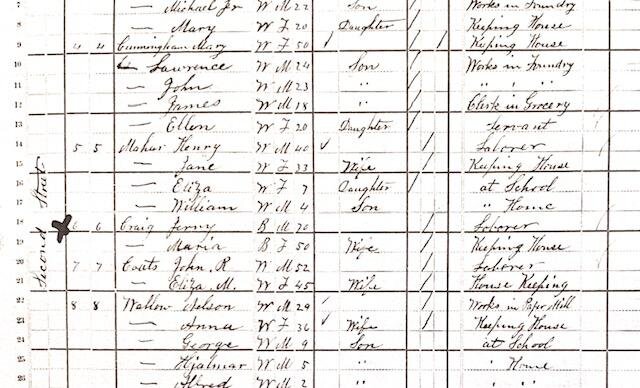

One of my objectives in starting this website is to add content to the context of these articles. This meant digging deeper into the narratives that have been written about Beloit’s African American first families. Some research trails led to nothing but dead end, but staying vigilant and not being afraid to go down what looks like a deep rabbit hole can be rewarding in many ways. While scouring ancestory.com for the name Emmanuel Craig, I found on the 1880 United States Federal Census a listing for a Jerry Craig, in Beloit, Rock, Wisconsin. Upon clicking on the document, it noted the following information, Jerry Craig, 70 years old, born about 1810 in Virginia. Race noted as black, married to Maria Craig living on Second Street in Beloit. Jerry’s occupation was listed as a “laborer” while it listed Maria’s occupation as “keeping house.” I also discovered a listings for a Jerry Craig (colored) living in Beloit, Rock County in the 1875 and 1885 Wisconsin State Census.

The most interesting finding was on findagrave.com for a “Jerry Creig.” The Find A Grave Memorial listed Jerry Creig, born 1775 in Virginia, died September 13, 1890 and is buried at Oakwood Cemetery in Beloit WI. It’s noted that Jerry Creig was buried on October 7, 1890 at the age of 115 years of age. These finding lead me to an article printed in the Minneapolis Observer, an African American newspaper published between 1829-1947. The following article was published on the front page, September 13, 1890;

“Five Score and Twelve Years Old

Beloit, Wis., Sept. 8-Jerry Craig, a colored man, whose age is given as 112 years,

died here Saturday.”

Find A Grave also listed an Ann M Creig buried on January 13, 1891, in Oakwood Cemetery. It states that Ann M Creig was born in 1790 and died Jan 1891. I believe that the initial “M” in Ann Creig’s name could possibly stand for Maria, the name listed as the spouse of Jerry Creig in the 1880 census. According to this record, both Jerry and Ann M Craig lived to become centenarians. The 1890 Hand-Book of Beloit includes a complete directory of heads of families it listed a Jerry Craig living at 313 Milwaukee. The book was published in August 1890, a month before Jerry Craig died. Prior to my findings of Jerry Craig, we only knew the name Emmanuel Craig being noted as the first African American known to live in Beloit. There were no records that I could find to support that claim of a person by the name of Emmanuel Craig living in Beloit in the mid to late 1800’s. Thus after years of research I conclude that Emmanuel Craig and Jerry Craig are one in the same, Beloit’s first African American along with his wife Ann Maria Craig.